Football's financial scandals of the 1960s

There is a rose-tinted view that football in the past was more honest than it is today, but nothing really could be further from the truth.

Every generation has its comfort blanket of nostalgia, and the idea that the past was in some way purer than the world in which we now live is an extremely common one. And football can be the absolute worst for this. Players kicking seven bells out of each other on grainy black and white video clips were ‘great characters’. Boring matches are eulogised on the basis of tiny highlights packages. And money is a corrosive influence on the game now in a way that wasn’t the case in the past.

In the first place, football was run by amateurs for amateurs. The idea of professionalism was considered a little gauche by those with the wealth to be able to play the game whenever they wanted without having to worry about the costs of living, to the point that it was banned until 1885, by which time there was a very real threat that newer clubs, primarily in working class areas and formed or run by members of the merchant class, would split from the FA altogether in much the same way that would later happen between rugby league and rugby union.

That split was averted, but it had been clear for some time that changes would have to come. The rules surrounding the way in which football was governed in this country had largely been set at the end of the previous century, but were increasingly looking outdated by the end of the 1950s. When football returned after the Second World War attendances had boomed, but that boom had, if anything, been somewhat short-lived, peaking in 1950 and being followed by a slow tail-off in numbers that would take decades to properly arrest.

The battles continued throughout the first half of the 20th century. There was a huge betting crisis in 1915 involving Liverpool and Manchester United which resulted in seven players being banned from playing for life. In 1919, Leeds City collapsed and were expelled by the Football League after the club's directors refused to co-operate in an FA inquiry and hand over the club's financial records over an inquiry into the club’s financial affairs over the previous few seasons.

But it would be the industrialisation of football throughout the 1950s and 1960s that would expose the fissures that had long existed between the lofty ideals of those running professional football in England and the reality of life in the post-war world. The creation of European competitions in the mid-1950s and the growing interest of television meant that by the end of that decade the game was having to start to face the reality that things were going to have to change.

Travelling abroad was easier than ever, and increasingly the very best players—John Charles, Jimmy Greaves and Denis Law among them—were being tempted abroad by wage offerings that massively outstripped anything that English clubs, who operated under the highly restrictive maximum wage and retain & transfer laws, which limited player earnings to those of a skilled tradesman and which allowed clubs to prevent players from leaving on any terms bar their own at the end of their contracts.

The maximum wage and retain & transfer had only been abolished after a credible threat of strike action by players and a high court case respectively, and those who were concerned about what might happen as a result of football operating a less restrictive contractual structures for players may well have felt vindicated when, in April 1964, The Sunday People newspaper reported that a League match between Ipswich Town and Sheffield Wednesday played 18 months earlier had been rigged.

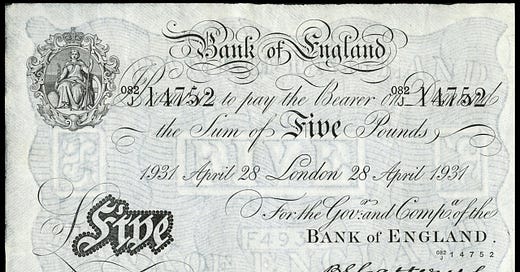

The story had been leaked to The Sunday People by Jimmy Gauld, a former player who in August 1963 had been outed in another report over match-fixing at Division Four club Hartlepool United as the ringleader of a syndicate betting on matches which were being fixed and who was chasing one final payday through selling his story to a national newspaper. Three Wednesday players, Peter Swan, Tony Kay and David Layne, had placed bets on their own side to lose against Ipswich. Their winnings amounted to just £100 each—£2,750, adjusted for inflation to 2025—but the response was swift and harsh.

Ten former or current players were finally sent for trial at the Nottingham Court of Assizes in early 1965. It would be the first time that taped evidence—of conversations recorded by Gauld—was admitted in an English court. At the end of the trial on the 26th January 1965, Gauld—described by the judge as the "central figure" in the case—received the heaviest sentence of all; four years in prison.

Brian Phillips of Mansfield Town and York City wing-half Jack Fountain were each sentenced to fifteen months in prison, Dick Beattie of St. Mirren received nine months, Sammy Chapman of Mansfield Town, Ron Howells of Walsall and Ken Thomson each received six-month sentences while David Layne, Tony Kay and Peter Swan each received four-month sentences. On release, Layne, Swan, Kay, Beattie, Fountain, Chapman and Howells were banned for life from any further participation in football. Gauld, Thomson and Phillips had already been banned. In total, 33 players were prosecuted.

And this was far from the only scandal involving the professional game to be making national newspaper headlines during that decade. The sudden and unexpected resignation of Accrington Stanley from the League in 1962, the first club to do so mid-season since the ill-fated Thames AFC in 1931, with the involvement of Football League Committee member and chairman of Burnley Bob Lord raising several eyebrows.

Lord had encouraged the Stanley board to tender their resignation from the League because their financial position was so terrible and the board agreed. Only after having done so, and with further advice having confirmed that such drastic action really wasn’t necessary, did they change their minds, but the League refused to allow them to retract the letter and they were gone. Accrington Stanley lurched on as a non-league club until 1966 before folding and having to be reformed.

In November 1967, the Football Association and Football League met to consider charges of making illegal payments to players, poor accounting practices and poor internal governance at Third Division Peterborough United, who’d only been members of the League since 1960 after having replaced Gateshead, stemming from claims surrounding an FA Cup match against Sunderland the previous January. Peterborough were demoted into the Fourth Division at the end of the 1967/68 season. They would have finished 6th otherwise.

At the start of the following year another joint inquiry, this time into the financial goings-on at Port Vale, found club officials being forced to admit several breaches of the rules regarding payment of players. The result was expulsion from the League, but before the start of the following season a vote of 39 to 9 allowed the club to be immediately readmitted to the competition. In Scotland, the merger of East Stirlingshire and Clydebank had proved extremely controversial, while the collapse of Third Lanark in 1967 after several years of mismanagement and neglect was a shock.

This feeling of grubbiness extended down into the non-league game in England, too. The end of the FA’s distinction between amateur and professional football came in 1974, but it had been a long time coming. More than a decade earlier, the over-excitable club president of Hitchin Town Syd Stapleton had crowed to a stranger who he didn’t know was a newspaper journalist that his team’s recent transfer from the Athenian to the Isthmian League would not have been possible without paying his players under the counter.

That the FA should have been alarmed by this was no great surprise. The widespread belief in the primacy of the ideal of amateurism was already rapidly fading by this point, but even those unconcerned by the principles of what was essentially cheating could see a whole other host of potential problems a little further down the line. If the Inland Revenue started to take a greater interest in all of this, the ramifications could be enormous in a tax evasion sense, if nothing else. Players, managers, chairmen and clubs themselves could all be swept up in this. Something had to be done.

By the early 1970s, there were three big amateur leagues left; the Isthmian and Athenian Leagues, in the south-east of England, and the Northern League, in the north-east. By this time there were players in these leagues who were routinely paid on the down low. “Boot money”—so named because cash would be left in players’ boots after matches—could amount to as much as £50 per game (£850, adjusted for inflation from 1972 to 2025) for the best players.

In 1972, the FA confirmed that the distinction between amateurism and professionalism would come to an end from the end of the 1973/74 season. The FA Amateur Cup would be abolished and replaced by the FA Vase, a knockout competition for smaller non-league clubs with a Wembley final to sit alongside the FA Trophy, which had existed for professional non-league clubs since 1969.

Amateur leagues and clubs could, of course, remain that way if they wanted, but that would be their decision and their decision alone. Of the big three amateur leagues, only the Northern League decided to hold fast, turning down repeated opportunities to join the non-league pyramid that was funnelling clubs up to a new top tier of the non-league game, to be called the Alliance Premier League, when that was formed in 1979.

The Isthmian League joined the Southern and Northern Premier Leagues as feeders to this league in 1982, but the Northern League held out for the rest of the decade, slowly decaying as its best clubs defected to the Northern Counties East League, which was within this nascent pyramid. By the time they finally did join the party in 1991 it was at a substantially lower level; in the current system, the league is a Step 5 league, as far from the National League—as the Alliance Premier League is now known—as the National League is from the Premier League.

Perhaps one day there will be a time when the modern game is looked at through this sort of lens. Perhaps it’s just the truth that wherever money and glamour are to be found, there always be will be those drawn towards it like flies towards a light. Perhaps that competitive edge is warped by its presence. Perhaps regulation will tidy up the messes in which clubs so frequently find themselves, or perhaps the clubs themselves will just find new ways to circumvent the regulator. If they do, they can at least rest assured that there’s a long history within the game of trying to do precisely that; certainly more of one than some nostalgists would like to admit.