Honours even in the New Home Town versus Old Home City Derby

Worthing and St Albans haven't got much in common other than that I grew up in one and now live in the other.

God bless rail replacement buses, he said, hypocritically.

Walking has been part of my normal daily life for as long as I can remember, and by that I mean walking. I grew in a village, two miles from school and four miles from town. Throughout my twenties, thirties and forties, that sort of distance felt like nothing. The only issue I had with it was the amount of time it took. But the times are a-changing. I’m in my fifties now, and walking that sort of distance is starting to have consequences.

I’m now 51 years old, and have lived roughly a third of my life in three different places, North London, Hertfordshire, and Sussex. My formative football years were spent at Enfield, but the team that I’ve seen more of by volume than any other, and by a comfortable distance, is St Albans City. I went to my first match there in 1982, three months after we moved to this house in a scrap metal yard, which was built in the yard of a former railway station. I only had the slightest inkling at that time of the extent to which rolled steel joist beams would play a significant role in the background aesthetics of my teenage years.

In those early years after we moved, getting back to Enfield was easy. We may have moved a few miles away but my two grandmothers, by this time both widowed, stayed where they were, in the same streets that they’d trodden for decades. We’d go up there together, do some shopping, and then walk down to grandma’s flat before my dad and I disappeared to the football. Then I started disappearing there on my own.

But time goes on and things change. I became a teenager, and part of forming my own identity was bonding with a group of friends of my own. I started going to watch St Albans more regularly from about 1985 or 1986. By about 1987, I was going to every match, home or away, usually on my own, and very often without speaking to anybody the entire afternoon, a peculiar practice which spoke a lot of my character, simultaneously gregarious and easily withdrawn, someone who passes through each and every day silently wondering why I should be blessed with two such violently contrasting sides to my personality.

The routine was straightforward enough. Match programmes had a guy’s name and telephone number printed in them. You just called that number and booked a place, and you were in, on a journey to some town or city, either on the outskirts of London or one of the counties that wrap round it like a belt. You’d then turned up at the appointed time, went to the match, met back again half an hour after the final whistle (just enough time for the old ‘uns—which was essentially everybody else—to grab one pint and no more, considering the coach journey head), and got home, normally about seven or eight in the evening. I carried on that strange little routine until 1990.

I’ve lived most of my life with fairly low expectations, and I do sometimes wonder to what extent St Albans City helped to shape this. Between 1986 and 1992—from when I was 14 until I was 20—they finished 14th, 15th, 17th, 15th, 16th and 13th. By the time they finished 2nd in 1993, the season of the tree (which occasionally still turns up in ‘did you knows’ on Twitter - note the now deceased link to my old place on the link there), I was a couple of hundred miles away at university. Three decades on, it is this story which seems destined to be the club’s most notable footnote in the lore of English football.

The 1992/93 season improved crowds, and they stayed inflated. Furthermore, other people my age started going. It would be a stretch to say that it became ‘fashionable’, but it stopped feeling like a dirty little secret too, and that was a start. Expectations rose a touch, too. The rest of the 1990s was spent in 6th or 7th place in the table rather than 16th or 17th. They even made it to the First Round of the FA Cup in 1996, though they conceded nine when they got there, at Bristol City. They got to within a hair’s breadth of Wembley in 1999, before losing the FA Trophy semi-final to Forest Green Rovers, and after leading in the second leg.

But during those six years of essentially my adolescence, what was really, truly notable was the absence of anything happening. They won two FA Cup matches throughout this period, in 1988/89 and 1991/92. In the FA Trophy, they got all the way through the three qualifying rounds in 1986/87, but then lost 6-0 to Welling United in the First Round and didn’t win another game in it for another five years.

And I never truly reflected upon what a strange practice of mine this was, to disappear for a quarter of every Saturday to go to some godforsaken non-league football ground, usually in the arse end of nowhere, always on a coach of men considerably older than me. One of the bigger selling points of going in my twenties was that at least I was going with people the same age as me, and usually by train.

I moved to London in 2001, but carried on working in St Albans for another five years. I started going to City less regularly, even though we only lived a short walk from a train back to the old town. But being there five days a week, sitting in an office wondering whether I should have considered a ‘career’ rather than a ‘job’ all those years ago and what problems that might be storing up for my future, at least kept me in touch until in 2006, we moved to Brighton. London took a bit much out of me, both physically and financially. Too much sex, drugs and rock & roll. Well, drugs and rock & roll, at least.

City were promoted into the Football Conference about three weeks after we moved, but I still had enough in me to be at that 2006 play-off final in Stevenage. I also had enough about me on the first day of the following season, too, to get up at an absurdly early hour of the morning to get a train to London and a coach to Birmingham for their first league game at that level, a surprisingly straightforward 3-1 win at Kidderminster. A couple of weeks later I was doing the same thing again, this time to Oxford. That time, they lost.

That Kidderminster win on the opening day of the season turned out to be the highlight of the season, as things turned out. They were relegated in bottom place that season, and haven’t darkened its doors again since. And although City have faded from my view, they’ve never completely disappeared from it. The internet, and in particular social media, makes that all but impossible. I’ve gotten up to Hertfordshire a handful of times over the years, most recently to see them serve up a dish served very cold indeed by knocking Forest Green Rovers, now an EFL club, out of the FA Cup live on the television.

This is the second time that they’ve been here this year. In February, with both teams jostling for a play-off place, City won 5-4 in one of the more remarkable games I’ve seen in the last few years. They ended the season in the final of the National League South play-offs, getting beaten 4-0 by Oxford City. Looking at Oxford’s position near the bottom of the National League table, it’s difficult to avoid the conclusion that the City who lost that match so heavily wouldn’t be having at least just as dismal a time of it.

So the rail replacement bus was useful, considering this very specific set of circumstances. I’d spent the day before tramping round Worthing in varying degrees of rain, and advanced as my years are, I’m still feeling it the following morning. The bus, a gratifyingly short walk from my house, drops me off a gratifyingly short walk from Worthing’s ground. We’re paid and in by 2.30. It actually is a Christmas miracle.

The ninety minutes that follows is an object lesson in what happens when two teams that are both blowing hot and cold collide. Worthing beat Chippenham comfortably here a week earlier, but lost 4-0 at Weston-super-Mare on Tuesday night. They’re on the cusp of the play-off places, but when they lose, they lose. The Weston hame marked the fifth time they’d conceded four goals this season.

City have had a dreadful run following a reasonable start as injuries have started to mount. But even so, they managed to pull a 3-2 win against second-placed Maidstone United out of somewhere in the midst of all that, so they’ve still clearly got something about them, even though at kick-off they’re 17th in the table, only five points above the relegation places.

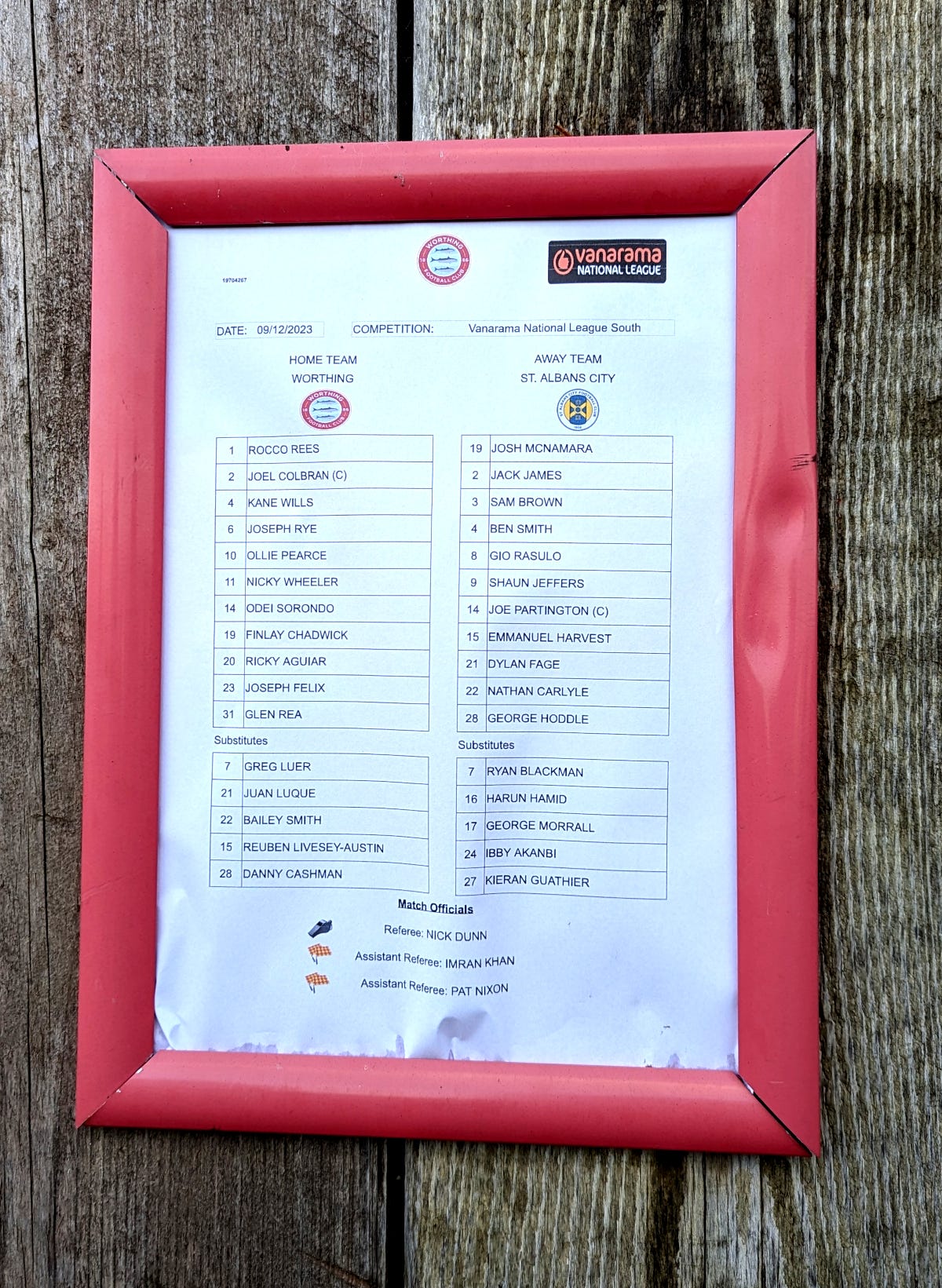

These are quite clearly two teams who cannot defend. Within ten minutes City are 2-0 up, the first of many defensive lapses followed by a 25-yard stunner from Shaun Jeffers, the popular striker who remains inexplicably unpopular with manager David Noble. But it doesn’t for a moment feel as though it’s going to last, and by half-time Worthing lead 3-2, thanks to one from Kane Wills and two for Ollie Pearce, the second-highest goalscorer in the division. Every time the ball gets anywhere either of the goals it feels as though just about anything could happen. The City supporters behind the goal are singing, “5-4, we’re gonna win 5-4” while they’re 2-0 up. Fans often know their team better than anybody else.

And there are familiar faces behind that goal. Older than they were, but still familiar. I stop and chat with Ben, a guy I played football with more than twenty years ago, before the match. He was one of the ‘youngsters’ at the time, no more than eighteen or nineteen years old. But we’re all varying degrees of middle-aged, nowadays. Good to see Wolfman there, as well. An object of permanence behind the goal at Clarence Park for surely more than thirty years. During that Forest Green Rovers FA Cup match he’d been standing relatively near us, imploring the referee to blow the final whistle when there were at least ten minutes still to play.

The gaps in the crowd around Woodside Road are noticeable. As at many other clubs, Worthing’s attendances rose sharply following the lifting of pandemic restrictions, and while this has tailed off somewhat elsewhere so far this season theirs had remained healthy. But Brighton are at home this afternoon, and while it may be that Christmas shopping (and perhaps even the ongoing cost of living crisis) is also taking a toll on this afternoon’s crowd, it seems likely that the Brighton match is as well. The irony is that those who’ve come to Woodside Road are getting considerably better value than those who made the trip over to the Amex, where the Albion end up chugging to an unspectacular draw against Burnley.

The second half is a slightly calmer affair, thugh this isn’t saying much. A defensive mix-up—yes, another one—allows George Hoddle, second cousin of Glenn, to level the scores at 3-3, but City can’t hold onto parity for long and four minutes later Ricky Aguiar restores their lead. But it all feel as though this lead is more fragile than it should be. Worthing dominate possession, but every time City break the Worthing defence gets into a flap.

With a couple of minutes to play goalkeeper Rocco Rees almost Schumachers one of his own defenders, only to see the ball bounce on goalwards regardless and have to be cleared off the line by one of their other defenders. But the warning isn’t heeded. Barely a minute later another one catches them similarly flat-footed and this time Ibby Akanbi, a former Worthing player no less, has plenty of time to relax, compose himself, and maybe eat a sandwich before sliding the ball past Rees to make it 4-4. Even then, deep into stoppage-time, the ball flashes across the City six-yard box, but Danny Cashman can’t quite get enough on it and it ends up in the side-netting, with the goal knocked off its moorings. The wheels on the goals do indeed go round and round, as had been observed from the away end during the first half. It finishes 4-4.

I trot down to the railway station, where a replacement bus is just about to leave. I’m home in time for kick-off in the evening game. I don’t have a two-hour journey on a coach, or a tortuous journey further by rail and bus this week. But while Worthing is home, it isn’t home. My dislocated life has probably left me without one of those, but those were the decisions I made when I was younger, and now I have kids of my own I recognise that this town, a perfectly nice place to live inhabited by largely pleasant people, is their home now, if nothing else.

It’s a strange reflection to end upon, that the very nature of the football supporter was forged in the 19th century, when life was more stratified and moving from one town to another was far from commonplace. But human nature, it would appear, is human nature. The football clubs of Sussex aren’t mine. I always feel like a visitor. And I don’t mean that as a criticism of anybody, including myself. There is something liberating about not being tied to one football club, to be able to enjoy the game entirely on its own terms and without having to spend as much of my time with my stomach tied tightly into a knot as so many of the rest of you.

But when home plays home, it turns out that home wins, even when they don’t.