Single Parenthood & I: The Invisible String That Connects Us

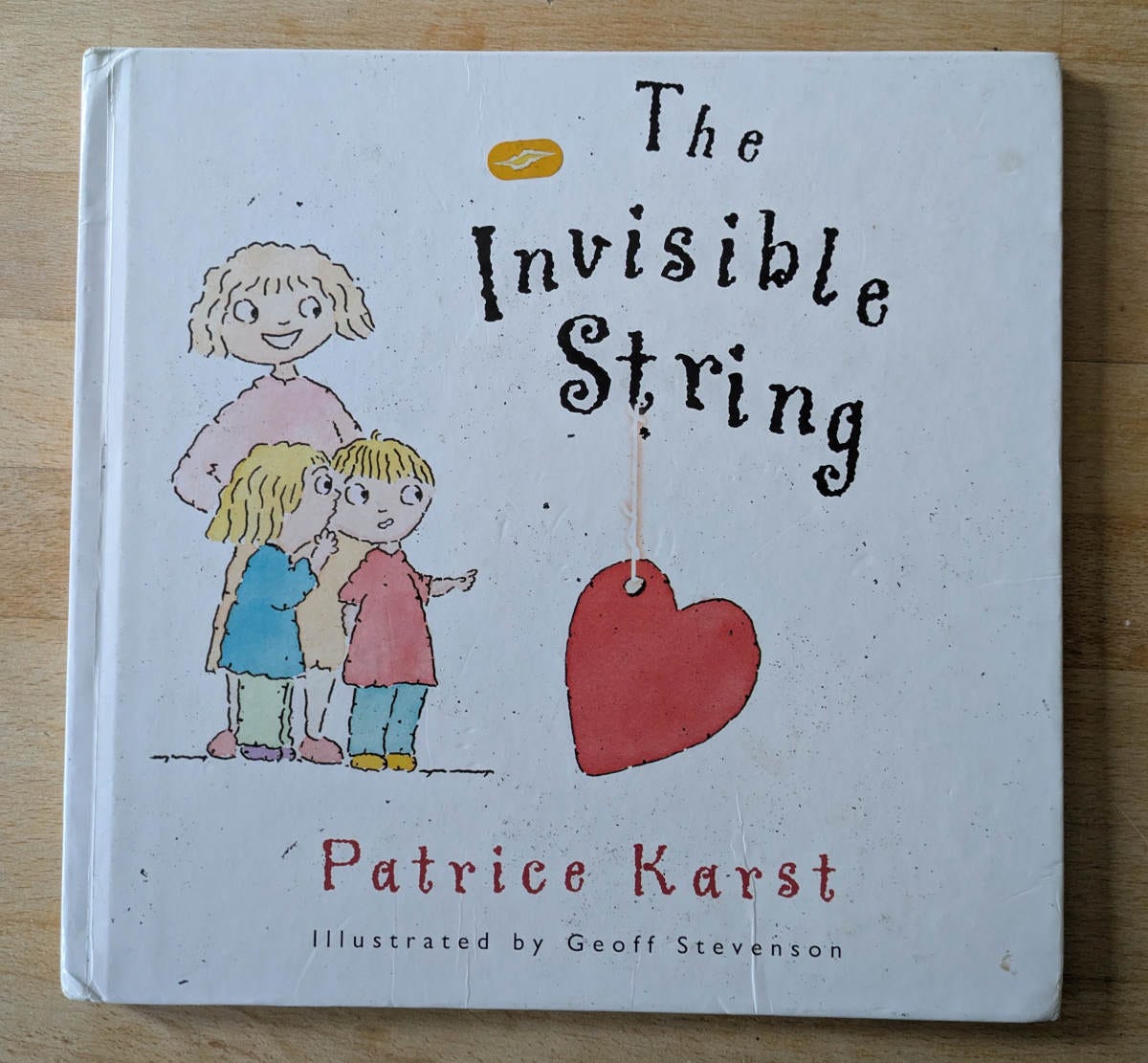

There's a children's book in our house which has taught me more about how to see the world and interpersonal relationships than any self-help book ever could.

I am, by nature, a fairly rational person. Show me something, and - subject to fact-checking - I’ll believe it to be true. For a while, I had a T-shirt that read “I Believe in Science.” I’ve never been avowedly atheist. I’m far too uncertain about everything for that. If anything, the absolute certainty of hardcore atheism is as much of a turn-off to me as the most prescriptive of religions.

The closest I have to a religious doctrine is that I’ll do my best throughout my life, and if that isn’t enough to satisfy whoever guards whatever afterlife there may or may not be when all this comes to an end, then I’ll just have to be reincarnated as a woodlouse or spend the rest of eternity having red hot pokers being shoved into uncomfortable places.

But as I’ve come to age, I’ve also started to believe that there is a lot that we don’t know about the universe and the energy that exists within it. I am, I like to think, genuinely open-minded. I certainly believe that there is a lot about the human brain that we have absolutely no chance whatsoever of understanding. And sometimes, whether something is strictly speaking, peer-reviewed true can feel like an irrelevance. Sometimes, what we really need is comfort, and a way of making sense of a universe that can be absolutely baffling in a variety of different ways.

For me, Invisible String theory falls into that category. It falls under the category of folklore rather than religion, and its roots can be traced back to East Asia, and in particular, China. It posits that the universe keeps two people apart until the timing is right, and that when you finally meet, there will be a series of uncanny coincidences as though coordinated by some form of higher power. It’s comforting, it’s whimsical and, critically, it doesn’t need to be true in any sort of literal sense to mean something.

I was introduced to it through my former mother-in-law. She lived in Florida and had never been expecting her youngest daughter to have children. She yearned to be with them, to the extent that she would travel to this country to see them, spending a week or two doting on them and loving them in the way that only a grandmother can.

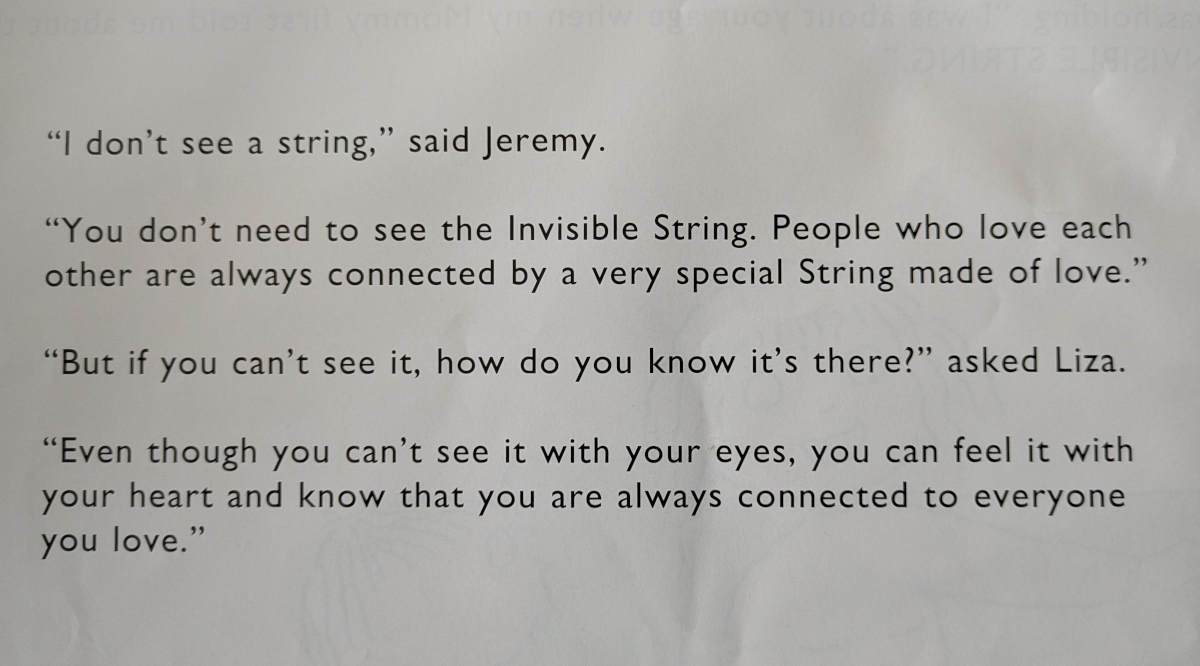

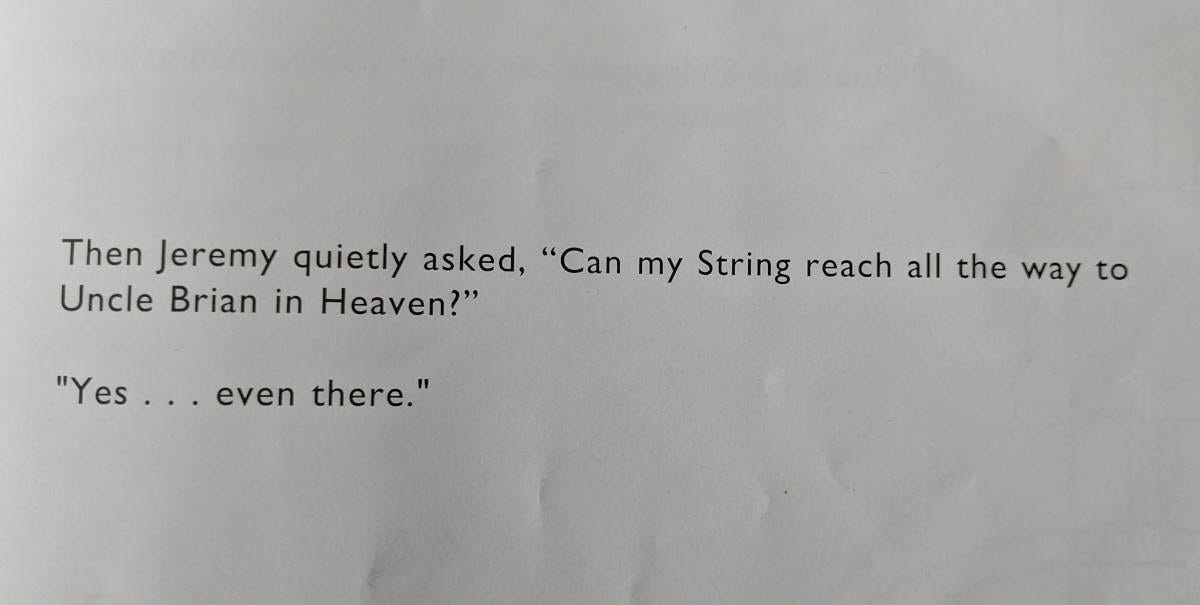

One book she bought them was called The Invisible String. I still have it. It’s one of the keepsakes of my kids’ early development, and I’ll never let it go. It is, as all children’s books are, a very simple and brief story. Two children in bed are scared by a thunderstorm and run down to find their mum, who reminds them that “people who love each other are always connected by a very special string made of love.” Satisfied with her explanation, they return to bed to ponder that “from deep inside, they now could clearly see… that no-one is ever alone.”

It’s a bit battered looking, this book, and inside the back cover have been drawn a series of cryptic pictures which only serve to reinforce my long-held belief that the Sulawesi cave paintings might have been the work of a five-year-old. But the messages contained between its covers have offered me solace for several years. And there’s a further message for those of us who feel distanced from those we love through bereavement.

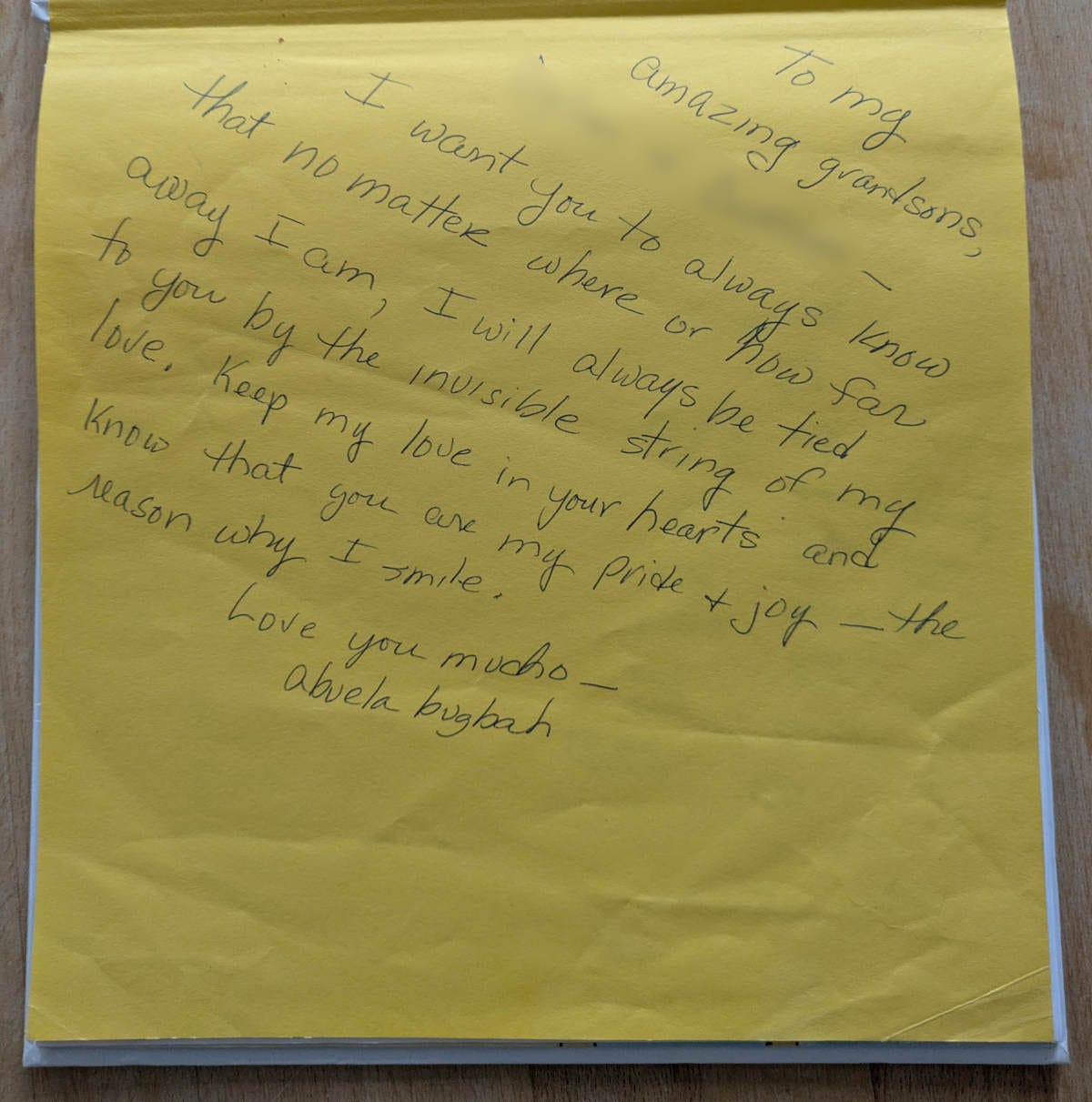

It’s hokey, because of course it is. It’s a bedtime story for kids. But I do feel powerfully attracted to the idea that we have a connection to those who we love which we can’t easily explain. The reason for this specific book being in our possession in the first place means a lot, as well. Abuela - she was half-Cuban and my ex-wife’s father is Cuban, so it mattered to all of us that she used the Spanish version of “grandma” - was thousands of miles from two children that she loved very, very deeply indeed, and it mattered very much to her that they knew that wherever they were, and wherever she was, their hearts were joined to her by this invisible string.

And there’s another message inside the inside cover of the book, which means more to me than words could ever really express.

Abuela died in 2023. But wherever she is now, in this universe that we don’t understand, they’ll always have this message, a reminder of someone who loved them very, very much indeed. Words written on paper can live forever, so long as the paper they’re written on is looked after. They still feel that love to this day. That string still exists.

In a sense, it’s one of the curses of having children later in life. My own mother died when the kids were just shy of two and four respectively. Younger can’t remember her at all. Older has a vague, half-formed memory of her. We have no such memento of her, only a couple of photographs of her with them, taken in the closing few months before she passed. One of their grandfathers is now 89, and in the process of being claimed by Alzheimers. The other one is in Florida. He is chronically ill, and they may never see him again.

When my mum died, I knew it was coming. Shortly before it happened, I asked for ten minutes alone with her in the hospital that she would never come to leave. I talked to her, with absolutely no idea of whether she could hear me or not, though I choose to believe that she did. I apologised for all the ways in which I might have let her down over the years, and I thanked her for everything that she’d done for me. And the very very last thing I said to her, the very last thing I knew that I needed her to hear, was that I hoped that she was proud of me.

Mum was 84 when she died. A decent knock, as they say in cricket. But although it was sad that she didn’t get to see her grandchildren start to really grow into the beautiful people that they are becoming, I have a lot to be grateful for. My parents were (and one of them remains) outstanding role models. Their marriage lasted until a month shy of what would have been their 60th wedding anniversary. When things went wrong, they worked together to fix them. Their love was - and remains, since that flame hasn’t snuffed out in the one who is still with us - deep, warm and abiding.

As I’ve got older, I’ve realised how lucky I’ve been with that. I know people who never even knew who their parents were. I know plenty of people who lost their parents at a distressingly young age. I know people who haven’t been able to grieve, or who haven’t wanted to. And to those people I’d say, try to remember that those pieces of string still exist. Remember Uncle Brian in heaven. I wouldn’t say that I believe that’s where he is, but I’m open to it, and if believing that he is does so, then I hope it helps you to find peace.

So many people, so much string.

Beautiful.