The Best Team in The Land & All The World, Part Seven: La Bombonera Massacre

For the second year in a row Estudiantes de La Plata were playing in the Intercontinental Cup in 1969, and this time the violence was such that the President of Argentina ended up involved.

This is a split piece. The first half, about the 1969 Intercontinental Cup, is available to all, but the second, about the events of later that evening and the following morning, is for paying subscribers only. It will be opened up to all next Wednesday.

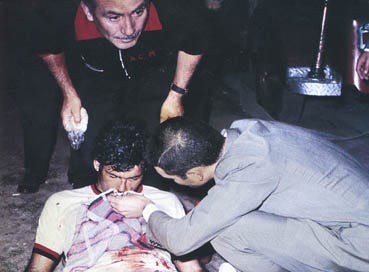

Néstor Combin was an accomplished footballer. He made over 400 appearances for some of Europe’s biggest clubs, including Lyon, Juventus and Torino and won the Coupe de France and the Coppa Italia twice, while being capped eight times for France. Yet the footnote that he is probably best remembered for within the history of the game is a photograph of him taken while playing for Milan which flashed around the world soon after the 22nd October 1969.

Milan had won the European Cup at a canter earlier in the year, demolishing Ajax 4-1 in front of a surprisingly small crowd of less than 32,000 in Madrid. It was their second European title, but it also threw them back into the Intercontinental Cup and two-legged final later in the year. And their opponents were familiar ones. Estudiantes had disgraced themselves in the previous year’s tie against Manchester United, but they’d won the Copa Libertadores at a canter, demolishing Nacional of Montevideo in a tournament again blighted by an absence of Brazilian teams.

Here we go again, then. But the first leg proved to be a strangely uncontroversial event. On the 8th October 1969, Milan blew Estudiantes away with a 3-0 win at the San Siro. They took an 8th minute lead through Angelo Sormani, with Combin adding a second right on half-time and Sormani a third, midway through the second half. Milan were, put simply, the better team from start to finish. It was about as uneventful as it could get.

But ahead of the second leg, the South American press found something to get het up about again. This time it was Argentinian players who played their football abroad, and while Combin might have played his entire career in Europe and been capped for France, he’d been born in the Argentinian city of Las Rosas and passed through the youth system at Colón de San Lorenzo before moving to Europe to seek his fortune.

He picked France for his international football in 1964 because he’d just signed for Lyon. Eligibility rules for international football were very different then to now, having only been strengthened to the principles of “one player, one career, one flag” at the FIFA Congress held during the 1962 World Cup in Chile, which came over unhappiness that high-profile players such as Ferenc Puskas and Alfredo di Stefano switching to Spain from Hungary and Argentina respectively.

In modern football, a three-goal deficit ahead of a second leg against what’s clearly a very, very strong team might be considered an opportunity for damage limitation, or to take a slightly longer view of things and rest some players. But this wasn’t any normal club. This was Estudiantes de La Plata, who had proved the year before the extent to which they were prepared to go in order to get a result.

They’d tried it on in the first leg, because of course they had. But conceding an early goal in front of a hostile Milanese crowd, and their attempts to spoil the game fell flat. Milan were able to take their foot off the pedal over the final twenty minutes, a comfortable win already assured.

The upshot of all this was, of course, that Combin became the target of the ire of both the Rioplatense media and fans alike before the first leg was even played. Of course, only a tiny number would have the time, means and desire to make the long trip to Europe for the first leg, but that wasn’t really the point, although it certainly didn’t help that Combin scored in the first leg. Ahead of the second leg in Buenos Aires. That win at all costs was stretched as far as it could go. The two weeks between the two legs was plenty of time. It certainly didn’t take the score in the first match to get in the way of the vituperation growing.

During that time, the Argentinian press had established that Combin had avoided military service by moving to Europe at 18 and had accused him as such some six years earlier and republished the story, labelling him a ‘draft-dodger’ and ‘traitor’. The public already hated the fact that he’d left the country and played both his club and international careers abroad. It might even be considered a moral justification for what turned out to be despicable behaviour on the night of the second leg.

Again, the match was switched to La Bombonera. Again, it didn’t make any difference in protecting the players that had travelled from Europe. A crowd of 45,000 made the atmosphere as hostile as possible. All the gamesmanship that had been carried out a year earlier was repeated, only with the volume turned up to eleven. When the Milan players took to the pitch they were showered with missiles and had hot coffee poured on them, while Estudiantes players kicked balls at them as they attempted to warm-up. Eventually, they had to curtail it.

Upon his team’s return from the first leg in Italy, the Estudiantes head coach Ozvaldo Zubeldía told reporters from the Argentinian magazine El Gráfico what he planned to say to his players ahead of the return match. “I think we have a 20% chance of success, but it will get much harder if we lose our heads,” he said. “The important thing is to keep calm, play well, try to win the game even if we cannot recover the aggregate deficit, give a good account of ourselves and don’t get anyone sent off. Play well, go out to win, but without losing control.”

To get out the way the actual football match itself very quickly–because that really is the least aspect of this entire evening–Gianni Rivera gave Milan the lead after half an hour, stretching their aggregate lead to 4-0, only for two Estudiantes goals in two minutes just before half-time scored by Marcos Concigliaro and Ramón Aguirre Suárez to whip up an already febrile crowd just ahead of the half-time break.

But for all this, Estudiantes couldn’t close the gap any further. Estudiantes won 2-1 on the night, but Milan won 4-2 on aggregate. And at least the organisers had done away with their ‘points’ system for deciding matches and replaced the method for determining the winners with aggregate scores instead the previous year, meaning that there was no need for a playoff match and, not inconceivably, an international incident. Though it’s never been confirmed one way or the other, it seems entirely plausible that Milan could have refused to play in one had this still been the case. They’d have been justified, had they done so.

Pierino Prati was knocked briefly unconscious early on and while the Estudiantes goalkeeper Alberto Poletti punched Milan's Gianni Rivera near the halfway line while his team were taking a corner. The South Americans attacked their opponents in the most literal sense at every opportunity. Several mass brawls erupted, and at one point the military had to be called on to the pitch to restore order.

But to say that this isn’t the full story of that evening is only scraping the surface. And paying subscribers get the full story of what else happened that night below the cut. But extraordinarily, Estudiantes were back again in the Intercontinental Cup the following season, though by this time European patience with this annual barroom brawl was starting to wear extremely thin indeed.

It’s hardly as though Néstor Combin was a shrinking violet. After all, the nickname given to him when he signed for Juventus in 1964 was "Il Selvaggio", or “the Savage”. But no player could have realistically gotten through 90 minutes of the sort of treatment that he received that evening. He was kicked and spat at, and his nose broken by a punch to the face by Ramon Suarez. Shortly before half-time he was to be found at the side of the pitch at La Bombonera, his shirt and shorts covered in blood, almost unconscious. He had to be carried back to the dressing room from the pitch on a stretcher.

Yet somehow, his evening was about to get worse. It was past midnight by the time the Milan players eventually left the stadium, but as they did so Combin was grabbed by six people and bundled into an unmarked green car. A fan leapt upon the bonnet to stop it leaving, and was hauled off by police and beaten. After a frantic chase around Buenos Aires trying to establish where he was being held–the answer to this question eventually turned out to be a military prison. He was charged with desertion.

There was no basis for this under Argentine law. Combin had served in the French army and under the terms of a reciprocal agreement between France and Argentina he had no obligation to the country in which he was born. Indeed, the fact that he wasn’t arrested the very minute his team’s plane touched down in the first place hints that there may even have been some who wanted him to get his beating before his arrest.

But this was also massive, massive overkill. The story had taken place too late for the newspapers on the morning following the match, but there was also a political dimension to it all that others maybe had not foreseen. Argentina had never hosted a World Cup before but had been awarded the 1978 tournament three years earlier at FIFA’s 1966 World Cup congress, and the government did not want it taken off them. By lunchtime, president Juan Carlos Onganía had ordered Combin’s release and he was driven to the airport to join his teammates on the flight home.

On this occasion, the anti-fútbol–as their ‘style’ of play had been christened by this time–employed by Estudiantes had failed. A picture of Combin, bloodied and barely conscious, flew around the world. Writing in the legendary Argentinian newspaper El Gráfico, sports editor Julio César Pasquato wrote:

Estudiantes ... that was not manhood, it was not temperament, it was not spirit... this has been apologetics for brutality and madness ... this has embarrassed us all and those responsible should be ashamed. If we really want to continue believing in something in the future, let's start by repudiating this unfortunate episode.

And this time there ramifications for Estudiantes. The government’s concerns about how this would look to FIFA were well-placed. Poletti received a life ban from playing international football, while Suárez received a five-year ban. At the request of the President, arrest warrants for Poletti, Suárez and Manera, who turned themselves in that afternoon. All three received 30-day jail sentences, though these were fairly quickly commuted. Argentina would host the 1978 World Cup, though whether they should been allowed to or not is a different matter.

In 2015, Raúl Horacio Madero blamed Combin as the instigator of the evening’s aggression through provoking Ramón Aguirre Suárez in the first match by saying, “negro, don't warm up anymore because in one month I earn the same money that you receive in two years”. El Negro was a disparaging nickname given to Suárez, who was of Paraguayan descent and had dark skin.

Considering how seriously Estudiantes took this tournament and the sullying of their reputation that evening, it is slightly surprising that it took this attempt at a defence took almost half a century to come forward. It would be all the more surprising when the same team, including the players who were sent to prison over their behaviour on that evening, would be playing for them in the same tournament again, the following year.